MENU TO FIDDLE STYLES:

...........................

Balkan Fiddle

ROMANIAN FIDDLE

Of all the Balkan countries Romania surely has the richest fiddle tradition. The mountainous terrain, the large size of the rural population and the relatively slow pace of industrial development and modernization have all contributed to the survival of a way of life which disappeared from the rest of Europe centuries ago.

As in much of south eastern Europe, much of the music making is in the hands of gypsies, and has been since the mid 19thC when gypsies first settled in the country in large numbers. In Romania gypsy musicians are known as lautari, from the word lauta, meaning violin. This already gives you an idea of the importance of the fiddle. Music is handed down as a profession from father to son; performances are given by groups or tarafs at weddings and parties. The typical traditional gypsy band consists of a lead violin (the primas), a second violin and/or viola, called a contra; a cymbalom, (a type of hammered dulcimer), and a bowed bass. Also occasionally heard is a taragot (sometimes described as a primitive wooden saxaphone); a nai or panpipe, and a cobza (a type of lute). The bagpipe was common among peasant musicians until the arrival of the violin. From the 19thC the clarinet and accordion also gradually made an appearance.ROMANIAN FIDDLE TECHNIQUES

The primas takes the main melody, enhancing it with chromatic runs, double stops, arpeggios, pizzicato, harmonics and the like- all performance tricks which could be improvised on the spot to enhance the performance. He conducts the rest of the band with an imperious nod of the head, a scowl or a flourish of the bow, directing dramatic changes of tempo and mood. One of the most impressive and characteristic techniques of the Romanian fiddler is the use of a single bow hair. The hair, well rosined, is tied in a loop around the G string. Instead of holding the bow, the right hand slowly pulls the hair, producing an eerie rasping sound. You can hear this to good effect on the opening track (Dance of the firemen) of Taraf de Haiduks’ album Band of Gypsies; in the famous 1992 documentary film Lacho Drom, and in a magnificent scene in the film Train de Vie, where a duel takes place between a gypsy and a klezmer band.

ROMANIAN FIDDLE TUNE TYPES

The principal vehicle for the primas to strut his stuff is the doina- a lyrical rubato improvisation; it can be either slow or fast. A typical format for a doina would be to have an extended single chord- perhaps a D minor, played low but fast by the cymbalom with an um-chah rhythm. Over this the violin is free to play slow or fast, high or low for as long as he likes. The whole thing moves up a minor third to G minor, then up to dizzying A flat diminished ( the dim. chord is very typical of Romanian music), finally to A (the dominant) and then back to D minor. The whole performance might have no set melody at all, and all the changes are directed by the leader.A slow doina, which is for listening only, is often followed immediately by a fast dance tune called a sirba, in 2/4 time. The most common dance is the hora ( a circle dance) which can be either fast or slow. There are also various dances in asymmetric time signatures, particularly in the south of the country where there is a string Bulgarian influence. The Invirtita, for example, can be in 7/8 time. It is worth noting that, being originally folk dances which were never written down, and being played by musicians with plenty of skill but no formal training in the classical sense, the concept of a strict time signature may be somewhat arbitrary and misleading. The slow hora, for example, has basically two beats to the bar, a long one and a short one. This could be written as ¾, but the effect would then be too much like a waltz. In the Balkan Dance music book (Elizik) these tunes are written in 5/8, but described as “between 5/8 and 3/4”.The only way to really get to grips with such rhythms is to listen to plenty of original recordings. My favourite tune in this style is the Hora Femeilor, a particularly haunting version of which was used as the theme music for the 1980’s TV series of Olivia Manning’s “Fortunes of War” (originally the Balkan Trilogy

CLEJANI AND THE TARAF DE HAIDOUKS

During the communist era many of the urban gypsy bands which had been playing in hotels and restaurants in the capital Bucharest were expanded to form state folk ensembles on the soviet model. The Institutuli do Folklor din Romania, for example, was an 80-piece folk orchestra formed in 1948, with a classically trained arranger and conductor, Victor Predescu. With state support such groups were able to make commercial recordings and tour internationally. However they were, inevitably, both cleaned up and watered down, giving an artificially sanitized version of what was really raw, dirty music with its feet firmly in the soil. The dictator Ciaucescu has a policy of deliberately cutting off many inconveniently placed rural villages from the modern conveniences of electricity and piped water, with a view to eventually eliminating them entirely. Ironically, this had the effect of helping to preserve the music and traditions of many of them, isolated as they were from outside musical influences. Thus it was that in the village of Clejani, south of Bucharest, there were around 200 gypsy musicians living amid squalor and poverty, surviving by playing weddings in the local area. Among them were lautari of incredible virtuosity, little touched by outside influences. The town had been first created by a wealthy Serbian Prince who had moved there with a large band of gypsy slaves, many of them musicians; it had been a legendary centre of lautari ever since. In 1989, immediately after the fall of Ciaucescu, two Belgian musicians, Stephane Karo and Michael Winter visited the village in search of this legend. The first gypsy musician they came across was the veteran, toothless fiddler Nicolae Neacsu, who was to become the lead musician of a 13-piece band including violinists, singers, accordion, cymbalom and bass. Garth Cartwright, in his book "Princes among Men-journeys with gypsy musicians" quotes Neacsu; "You don't learn this job, you steal it. A true lautar is one who, when he hears a tune, goes straight home and replays it from memory. The one who plays it certainly won't teach you! Yes, the violin is light in your hand, but heavy to learn. Like mathematics!"With this group, named the Taraf de Haidouks (“band of brigands”), they made recordings and arranged a tour in western Europe. Their music was a huge success; in contrast to the state folklore ensembles, the Taraf come over as extremely spontaneous, undiluted and unprocessed. Numerous cd’s, tours and media triumphs have followed, and they have deservedly built an international reputation as simply the best gypsy band in the world. Johnny Depp, a big fan of the band, said of them "These guys can play a music which expresses the most intense joy. They are among the most extraordinary people I have ever met."

TARAF DE

HAIDOUKS

BULGARIAN FIDDLE

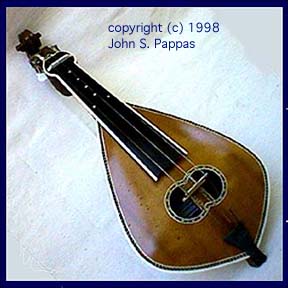

The Gadulka is a type of fiddle, played vertically either resting on the knee or held by a sling around the neck. The body is pear-shaped, quite similar to a Greek lyra. There is no fingerboard, and the strings are stopped with the fingertips or back of the fingernails, allowing for smooth sliding between notes, but making it extremely difficult for a violinist to master. The three melody strings are usually tuned AEA. There are also a number of sympathetic strings (between 10 and 12) which lie underneath the melody strings. These are not fingered, but ring on their own as the instrument is being played. They are tuned chromatically between A and E. There are two round or oval sound holes on either side of the bridge called ochi (eyes)Bulgarian fiddle-the Gadulka The gadulka is used either as a melody instrument or as part of the accompaniment for singing. Originally all village instrumentalists would have been amateurs, but in communist times many of the best players were given jobs as full time musicians, either in the state radio orchestra, or a similar ensemble. One of the first Bulgarian instrumental groups to visit the west was Balkana, a five-piece group with a line-up of gadulaka, gaida, tambura ( a long-necked lute, a bit like a Greek bazouki) and tapan ( a two-sided drum). The group toured with Trio Bulgarka, three of the singers who had featured in the Koutev’s "Mystere de Voix Bulgaire"choir. Mihail Marinov was the gadulka player. I was lucky enough to see them on their first tour in England, and was amazed by the dexterity of the gadulka playing. As a violinist you are taught that accuracy and position changing absolutely requires the fiddle to be firmly under the chin, and that folk players who play down on the chest do so at the expense of any advanced left-hand technique. To see a fiddler effectively playing with the instrument upside down, yet with amazing agility is quite an eye-opener.

Another star of the gadulka is Nocola Parov, who formed the group Zsaratnok in the 80’s. He began collaborating with the Irish folk musician and founder member of Planxty, Andy Irvine, who in his youth had spent some time travelling in Bulgaria, soaking up the wine and the music in equal measure. Parov and Irvine, along with writer and keyboard player Bill Whelan recorded a crossover album East Wind. This in turn led to Parov being included in Whelan’s successful scheme for world domination, Riverdance.The state’s promotion and modernisation of traditional Bulgarian music was not confined to the elite folk choirs and orchestras in the capital Sofia. In the villages too, musicians and singers were encouraged to indulge in “artistic amateurism”, performing for local events and celebrations. Instruments such as the gadulka, gaida and kaval were manufactured to new high standards, giving more regularity of pitch and intonation. In 1965 a national festival was established at Koprivshtitsa, in the Sredna Gora mountains. Held every five years, this is a spectacular all singing, all dancing event at which groups from all regions of Bulgaria perform and compete.

BULGARIAN GYPSY MUSIC

And what of the gypsies? We’ve already seen their importance in Romania to professional music making. In Bulgaria the state, obsessed with cultural and ethnic purity, fought a running battle for decades to repress both gypsies and their music. Whilst the music of ethnic Bulgars within the villages was seen as pure and symbolic of the nation, gypsy music, performed at weddings throughout the country was viewed as decadent, subversive and foreign. At various times the government even denied that any gypsies existed, claiming that they had been successfully absorbed into the proletariat. Nothing could be further from the truth. By the 1980’s, as the cracks were beginning to appear in the socialist monolith, there were several hundred gypsy wedding bands, operating largely on a free market basis, beyond the control of the state. Despite being deliberately cut off from benefits such as healthcare and pensions, and having their music described as “devoid of artistic value”, the demand for these wedding bands became almost obsessive, with the top musicians being able to charge huge fees.

The music played by the wedding bands differed from “approved” traditional Bulgarian music in several ways. The singing was far more emotional, the playing more improvisational, and the style much broader. Influences from the neighbouring countries of Turkey, Albania, Serbia and Macedonia were all present, as well as Western pop, rock and jazz feels. One rhythm particularly associated with the wedding bands is the cocek; a 4/4 beat split 123,123,12, giving it a strong oriental feel. The instrumentation of these bands, whilst often including acoustic elements such as accordion, violin or gadulka, also has electric guitars, drums and keyboards, and is amplified to ear-splitting volume.

The undisputed king of the Bulgarian wedding bands was clarinet player Ivo Papazov. He developed a remarkable combination of Balkan melody with bebop improvisation, playing at breakneck pace and with immense virtuosity. Whilst the traditional music of the state ensembles was calm, controlled and disciplined, his is wild, aggressive and highly individualistic- almost a deliberate provocation to the authorities. The collapse of the communist government in 1990 finally led to the end of the restrictions on travel and employment for the gypsy musicians, allowing them to tour in the west. At the same time, unfortunately the associated economic shock meant that few families could now afford the week-long weddings which had boomed in the 80’s, and the good times for the gypsy bands, ironically, seem to be over.BULGARIAN TIME SIGNATURES

For the westerner, there is one feature above all which makes Bulgarian music, along with that of neighbouring Macedonia, so fascinating. Most European folk music has time signatures of 2/4, 3/4, 4/4 or 6/8. The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s jazz hit “Take Five” 1n 1959 was considered revolutionary in the west, and had a generation of young hip intellectuals congratulating themselves when they finally got the hang of counting five beats to the bar. In the Balkans 5/4 was absolute child’s play; real men (and women) danced, sang and played effortlessly in 7/8, 11/8, 13/8 and 15/8…to infinity and beyond!The key to getting on top of these rhythms is to break them down into groups of 2 and 3 beats. A 7/8 tune , for example, is usually counted 123,12,12 (which you could also write as 3,2,2). It could also be 12,12,123, depending on how the melody is phrased. Fortunately most tunes keep a single rhythmic pattern, though some might change unexpectedly. Traditional musicians tend to think of these beats as combinations of quick (12) and slow (123) beats. The bad news is that this sometimes means the rhythm as actually played may not actually fall into any of the neat and exact patterns demanded by classically trained musicians.

Here’s a quick tour of some of the main rhythms. In most cases the accent will come on every 1, with the strongest accents on the 1 of every 3. Most of the rhythms are used for circle dances called horos or oros.. A typical tune title will therefore be Paidushko Oro, meaning, dance in the Paidushka rhythm.

5/8; the Paidushko – also known as the “Old Man’s hobble” or “the lame one”. Phrased 12,123. Traditionally a men’s dance; it is named after a village in north east Bulgaria

6/8; the Pravo; this is one of the most basic wedding dances- usually written in 2/4 with triplets.

7/8; if split 12,12,123 this is a Ruchenitsa, a couple dance named after the village of the same name in S E Bulgaria. If 123,12,12 it’s a Cetvorno. 7/8 is possibly the most common of the asymmetric time signatures; if you’re going to try and master just one of them, this is it.

4/4 or 8/8; the Cocek, a very popular dance associated with gypsy wedding bands, is split 123,123,12, reflecting a strong Turkish influence. In Alabania and Bosnia it is called Usul Derveshi, and was once used in the rituals of the “whirling” Dervishes.

9/8. Variously called the Gruncarsco, Svornato or Daicovo. This rhythm, 12,12,12,123 was almost certainly introduced from Turkey, where it is called Usul Kusten, and is widely used in both folk and classical music

10/8. Also introduced from Turkey, this rhythm 123,12,12,123, the Aramaska Cocuk, is danced only by women

11/8. The Kopanica, or Jedenaistvo (“the 11-beat one”) 12,12,123,12,12.A line dance.

13/8. The Postupano, from central Macedonia; 12,12,12,123,12,12. I find it helpful to create a mnemonic- a spoken phrase which makes it easy to remember the rhythm. This one could be “eating through piles of biscuits”

15/8. Bucimis ; 12,12,12,12,123,12,12

25/16 Sedi Donka; 123,12,12,123,12,12,12,12,123,12,12. Two questions loom large. How?, and Why! This rhythm qualifies as an extreme sport, alongside naked bungee jumping and freestyle bear wrestling.

SERBIAN FIDDLE

THE GUSLE

When Radovan Karadzic, (notorious fugitive war criminal or Serb nationalist hero, depending on your point of view) was in hiding in the disguise of bearded mystic Dragan David Dabic, his favourite pub was the Luda Kuca, “The MadHouse”. The walls of the tiny Belgrade bar are lined with portraits of nationalist icons, and it was here that Karadzic would sometimes entertain his fellow drinkers on the gusle (rhymes with loosely), the one-stringed fiddle which is itself a symbol of the historic struggle of the Serb people, whether against medieval Turkish invaders or Nato bombers.

A Gusle being performed in "The Madhouse" The bearded mystic The gusle is an ancient instrument, possibly a direct descendant of the first bowed fiddles of central Asia, Certainly it bears a resemblance to the Mongol horse-head fiddle, the Morin Khuur. It arrived in the Slavic lands of eastern Europe in the 8th or 9th C, and is used to accompany the singing of epic ballads.

The gusle has a round-backed wooden body, usually of maple and often intricately carved. An animal skin, often goat, covers the front, and there is a long thin neck topped by an elaborate carving of an eagle or horse head. The single (or occasionally double) string is made from thirty strands of horse hair. The bow is one of the most intricate that I have seen on any fiddle, short but deeply curved and with a distinct handle. There is no fingerboard, so, like the gadulka or lyra the string is stopped from the side by the back of the fingernail. The playable range is about a fifth.

The instrument is played upright, with the body resting between the player’s knees. It is found not only in Serbia, but also in neighbouring Croatia, Bosnia, Hertzegovina, Montenegro and Albania. In each country it is used to tell epic poems of historic struggle, tragedy, massacre and heroic survival. The singers of such songs are called guslars, and a successful performance will not only draw large crowds, but will leave them weeping. In many Serbian and Montenegran homes the gusle hangs on the wall alongside the hunting rifle and the antique sword, a symbol of all that is great and good about the nation. To many young people in these same homes it is something deeply old fashioned, described by one Serbian friend of mine as “An annoying noise which helps to keep you from falling asleep during the endless song of the guslar”

SERBIAN GYPSY VIOLIN

Serbia is best known musically for its gypsy brass bands, an inheritance from Turkish military bands in the 19thC. However, violin is also an important folk instrument. Among the best known Serbian gypsy violinists of the 20thC was Aleksandar Aca Sisic.

In the Balkans, as elsewhere the gypsies are subject to a great deal of discrimination and contempt, Despite all his publicity suggesting the contrary, Sisic, when interviewed by Garth Cartwright for his book “Princes among Men-journeys with gypsy musicians”, vehemently denied being a gypsy. Aca came from a long line of violinists dating back to the Austro-Hungarian empire. He was already playing a full-sized violin at the age of 5, and by 8 he was leading his own band. As a child during WW2 he recalls being hoisted up onto fascist tanks and told to play for the occupiers- after which there was no such thing as a tough audience! He thrived during Tito’s time, playing for the TV Folklore Orchestra and touring the world. He was particularly welcomed in Mexico, where “on every corner was a violinist, and I felt like one of them”

CROATIAN FIDDLE

The Lijerica (pronounced lee-air-itza) is a pear-shaped, three-stringed fiddle found in the mountainous and coastal areas of Dalmatia (part of Croatia) and Hercegovina.

It bears a close resemblance to the lyra of Crete, and is believed to have been introduced from Greece in the 18thC, spreading around the Adriatic coast in the 19thC. It is still used for the accompaniment of dancing in the area around Dubrivnik, and on some of the islands. It is played by the dance master, who sits in the centre of the circle of dancers. He plays with the lijerica on his left knee, stamping his foot to give the rhythm, and calling out instructions- often in rhyming verse, and often with a bawdy innuendo. The specific dance performed in Croatia is the Lindjo, the more general term for circle dances (used throughout the Balkans) being the Kolo. There is also a chain dance performed on some of the islands, where the dancers parade through the narrow village streets lead by the dancing master, who in this case plays the lijerica in a standing position.Traditional music and dance was encouraged in Socialist times, but has been under threat, particularly since the wars of 1990-95, when Croatia began to deliberately modernise and westernise its culture and economy. Nicholas Petrish, a third-generation Croatian now living in the US, is both a maker and player of the Lijerica, a singer and dancer, having studied with masters both in the US and in Croatia. In 2004 he gave 30 lijericas to Croatian children as part of a drive to preserve and stimulate the tradition.

The lijerica has also found its way into more popular, western-oriented music. Ivo Letunik, considered by many to be the best player in Croatia, works in the band Kries, playing a sort of hippy rock world music fusion, alongside English fiddler Martin Swan.

GREEK FIDDLE

Of all the European fiddle styles, that of Greece surely must be the most challenging and exotic, combining not only the complex rhythms found throughout the Balkans with scales borrowed from the arab world, but also the extensive use of sliding between notes.

The roots of music theory itself date back to the Ancient Greeks, when the mathematician Pythagoras used a monochord ( a single string with a moveable bridge, stretched over a soundbox) to demonstrate the principles of harmony. The monochord continued to be used into medieval times and beyond, eventually being bowed rather than plucked.

One of the great delights and challenges which arises out of this ancient music theory is the continued use of non-tempered scales in Greek traditional music. Scales, as played on the fiddle, are based on natural harmonics (unlike the modern tempered scale, which is a messy compromise to allow use of harmony). The major third, for example, is frequently played slightly flat of where you would find it on the piano. In the Hijaz mode the 2nd, 3rd and 6th are all different from standard. When written down, this is sometimes denoted in the key signature by a reversed flat sign in brackets, indicating that this note should always be played slightly flat. This is referred to as the vou/segiah note

Greek fiddlers frequently use very low bow pressure, in order to access the natural harmonics on which these scales are based.

GREEK DANCE

Traditional dance has been, and remains, an essential part of Greek popular culture. Plato said "Fancing is divine in its nature and is the gift of the Gods". Every region, and even almost every village has its own distinctive blend of dances and accompanying tunes. There are said to be at least 10,000 different dances. Some dances are unique to a particular location, whilst others are "pan Hellenic"- existing, with variations, all across the country.

Many dances are associated with particular social occasions or functions, such as weddings, religious festivals , the curing of the sick, celebrating war and victory and so on. They may also refer to specific occupations.

The Khasapikos/Hasapiko, for example, is the Butcher's Dance, which started in Istanbul and is still mostly associated with that city. It was originally intended to imitate the use of swords in battle. It is very close in feel and modality to some klezmer tunes. It is often slow, but speeding up towards the end.

One of the most popular and attractive dances to non-Greeks is the Kalamatianos, a leaping dance in 7/8 time (split 3,2,2) . It is named after the town of Kalamata in southern Greece, also famed for its delicious olives. Tunes and dances in 7/8 are common throughout Greece, but other complex time signatures, such as 5/4, 11/8 and so on, are mainly found in Phyrum, which is the Greek name for the former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia.

The Zeimpekiko is named after the Zeybeks, rebel bandits from Anatolia, in modern day Turkey. It is a slow dance, nowadays mostly played on the bazouko, with a 9/8 or 9/4 rhythm. This is split 2,2,2,3 or 3,2,2,2. It is an athletic solo dance.

The Syrtos is one of the most widespread, often considered Greece's national dance. The name refers to pulling or dragging. It has similar steps to the Kalamatianos, but is in 2 or 4 time, and is more smooth and flowing.

Rebetika

One of the most important branches of Greek folk/roots/popular music of the 20thC was rebetika. In its most accessible form this is the happy, sunny bouzouki music of Zorba the Greek and Never on a Sunday, but the origins if this style are dark and dirty. It originated among the Greek refugees from Asia Minor/Anatolia (now Turkey) following the momentous population exchange between those two countries in 1923. These new arrivals, though Greek by descent, formed a new urban underclass, ending up in the slums, hash dens, brothels and prisons of Piraeus, Thessaloniki and Athens. They created a new musical style often compared to the blues, with its themes of poverty, dispossession and despair.

Thought the instrument most commonly associated with rebetika is the bouzouki, the fiddle is also a key feature of many recordings. Two names in particular- Ioannis Dragatsis (also known as Ogdontakis) and Dimitris Semsis (Salonikios)- appear on hundreds of recordings from the 1920’s and 30’s. They make use of a complex array of Anatolian and Greek scales and modes. One mode in particular, the Smyrnian Minore (the wonderfully descriptive ”minor of the dawn”), is attributed to a late 19thC violinist Giovanikas. He combined for the first time the chords of gypsy, Balkan and western music with the oriental, monophonic “Niavent dhromos” mode. The playing style on rebetika recordings makes frequent use of high positions, and is highly ornamented.

Dimitri Semsis

A fine exponent of rebetiko violin today is Kyriakos Gouventas. Born in Thessaloniki in 1966, he had a classical training at the state Conservatory, going on to work in various orchestras and chamber ensembles. He also however developed a keen interest in various folk styles, including rebetika, dimotiko and smyrnaiko. He plays with traditional Greek dance groups, and, as part of the group Primavera en Salonico he has toured the world, accompanying the popular singer Savina Yannatou. Here he is, trilling like a lark with the ‘Mediterranean Trio" at the Parathin Alos music festival in 2008.

The story of Greek fiddle playing is also greatly enriched by the presence of two ethnic “knee fiddles”- the Cretan Lyra and the Black Sea or Pontic Fiddle.

The Cretan Lyra

On the Greek island of Crete, the lyra (pronounced lee-rah, and nothing to do with a lyre!) has become something of a national

symbol. It has a small, pear-shaped body and a very short neck. Constructed of mulberry wood, ivy or wild pear, it has two semicircular sound holes or "eyes". It looks in fact very similar to the Bulgarian gadulka, but does not usually have the sympathetic strings.

The Lyra is played upright, usually supported on the knee, where it is rotated as the player changes from one string to another. The three strings are pressed from the side with the fingernails, and are not pressed onto the fingerboard. This allows for a great deal of slipping and sliding between notes, giving the lyra a distinctive edge to what is otherwise a very fiddle-like sound. It is usually tuned GDA, and traditionally most of the melody was played on the first (top) string, the other two being used for drones or parallel harmonies. The convex bow often has small bells attached to it to provide rhythmic accompaniment to the melody. The bow strokes are usually short , rhythmic and mostly at the tip, by comparison with the longer, more fluid bowing of the Turkish Kemanche. Then lyra was once common in many parts of Greece, but today is mainly restricted to an arc of islands on the Aegean, which as well as Crete includes Kárpathos, Khálki, and Kássos. It is most often accompanied by a large mandolin-like instrument, the Cretan laouto.

Cretan Lyra by M. Stagakis, 1981 Probably the most famous lyra player was the late Kostas Moundakis; one of the best known players today is one of his former students, the remarkable Ross Daly who, despite the obvious disadvantage of his Irish descent, has settled in Greece and mastered not only the lyra but also the kemence, rebab and a whole menagerie of other exotic Mediterranean instruments. He brings together many of the traditions described above in ambitious and absorbing compositions of what he calls "contemporary modal music...musical voyages beyond multicultural fashions..."

Ross Daly

The Pontos is the area of Asia Minor settled by the ancient Greeks. Here a long, thin, boat shaped fiddle, usually tuned in fourths; GDA or AEB, is called the Black Sea Fiddle, Pontic Lyra or Karadeziz Kemencesi The extensive use of double -stopped parallel 4ths is an important feature of the playing of this instrument, with lots of trills on the upper notes. The strings are pressed straight down onto the fingerboard like a violin, making this much easier to play than most of the other lyras and kemenches, despite being held upside down. It is often played sitting down, with the fiddle balanced on the knee, but can be played standing up; some players can even dance and play simultaneously.

The music tends to be fast and energetic, with tunes in 4/4, 5/4, 7/8 and 9/8.There are a couple of other, less well known fiddles in Greece. The Lyra Drama is found close to Bulgaria; Drama is a city and municipality in north eastern Greece. This lyra is tuned EGE.

There is also the Karpathos Lyra, which has bells attached. This is tuned AAE.

Return to fiddlingaround.co.uk homepage

Chris Haigh is a London-based fiddle player who specialises in Klezmer, gypsy and East European styles. He plays with a trio, Klezmania, doing lots of Jewish weddings and Bar Mitzvahs; this band does a mixture of traditional Klezmer and Israeli tunes along with some jazz improvisation. Tziganarama is Chris's own trio, playing a wide range of Jewish, Russian, Balkan and gypsy music.

Chris sometimes plays solo or as a duo with accordion, going "around the tables" at a dinner.

He gives workshops on klezmer, gypsy and other east european fiddle styles, demonstrating techniques and ornamentation, describing the different tunes types and scales.

He writes original klezmer melodies; his tune "Klezmania" was used on a worldwide TV ad for Nike!

Eastern European Fiddle Tunes-80 Traditional Pieces for Violin BK/CD (Schott World Music Series)

Pete Cooper hooks us right from the start, with a folk tale of gypsies, fiddles, and the devil. Fiddling in eastern Europe is more than just a bit of light entertainment; it’s the stuff of history, magic and legend. Cooper immediately banishes the idea that there is a single east European style; it ranges from the virtuosic semi –classical gypsy fiddling to relatively basic and rootsy folk playing. For those nervous of venturing much beyond first position, you’ll be pleased to hear that this book is geared more towards the latter than the former end of the spectrum. MORE...

200 instrumental tunes from Thrace, Macedonia, Epirus, Thessaly, Central Greece and the Peloponnese.

By Lamprogiannis Pefanis and Stefanos Fevgalas.

Greece has one of the richest and most varied bodies of traditional music and dance in Europe- there are estimated to be at least 10,000 recorded dances.

In 2014, Pefanis and Fevgalas produced volume 1, a collection of 184 tunes from the Greek Islands (Crete, Cyprus, the Aegean, the Aegean, Ionian and other islands.). Volume 2 concludes this monumental work, with 200 tunes from all parts of the Greek mainland.

In the modern world there is an almost irresistible force of homogenization affecting all traditional music, no matter where it comes from. The huge diversity and individuality of local Greek music, partly a result of separation by mountain or by sea, stands in danger of being simplified and eroded. In this book, the authors have deliberately stood against this trend, by producing accurate transcriptions of classic recordings made at a time when the music was still largely aural in its transmission.

“Our intention here has been to give as clear a depiction as possible of the musical mode of expression of earlier generations…”

These recordings come from a variety of instruments- mostly clarinet, violin, lyra and gaida. In some cases they have, for reasons of practicality, changed the keys from the original, and, in the case for example of tunes taken from the lyra, drones have been omitted. However, basic ornamentation is included throughout, with a brief explanation in the opening text. Many of these tunes are modal, and the authors have followed the convention of including both sharps and flats in the key signature, together, rather than (as is the case, for example, in klezmer books) of putting flats in the key signature and sharps as accidentals within the music.

The collection is divided by region, and in each grouping there is a good representation of a wide range of dances, such as the Syrto, Chasapiko, Kalamatianos, Zeimpekiko and so on. The title often refers to the specific location or the source recording. The table of contents includes an English translation of the titles, though these are not used in the body of the book, so a non Greek speaker has to keep referring back. The opening text is also translated, as is the extensive discography and list of source musicians at the end.

This is not a book for the faint-hearted. If you’re looking for a simple introduction to Greek dance music, this is not for you. A few of the tunes are in bite-sized portions, but many are three of four pages in length, with little or no repetition- your sight reading skills will be well tested! There is a considerable range of difficulty; it is perhaps unfortunate that many of the hardest tunes are at the start, while the Macedonian tunes in the second half are considerably more straightforward.

Nevertheless, is you an experienced player of Greek traditional music, the depth, ambition and thoroughness of this impressive collection is something you are unlikely to see anywhere else.