MENU TO FIDDLE STYLES:

Middle East and Mediterranean fiddle

This large and complex area, incorporating many different countries, cultures and traditions, is as musically rich and diverse as its people. Whilst the violin is deeply rooted in many of these traditions, it has to share living space with many of its more exotic cousins, notably the rebab, kemanche and lyra.

Rebab

Of these the rebab (or rebap, rabab, rababah or al-rababa depending on your point of view) is probably the oldest, dating at least as far back as the 8th Century, when it was found in Arabia and Persia. It is almost certainly the direct ancestor of the European violin. Islamic trading routes helped to spread it over much of North Africa, the Middle and Far East from the 10th Century onwards.

The rebab was adopted as a key instrument in the serious classical music of the Arabs, along with such instruments as the oud (classic arab lute), the ney (end-blown flute) and various percussion instruments. Much arab music is based on the style developed in Andalucia during the Muslim occupation of Spain around 1000 years ago, and includes instrumental passages, usually with a strong element of improvisation, alternating with sung poetry. Improvisations or taksim are based on a complex system of modes and rhythms. The melodic modes or maqamat have different combinations of 24 possible quarter notes, and each has its own mood, often associated with particular feelings or seasons. One hundred and eleven rhythmic patterns or iquala can be used; the simplest of these is the rajaz, based on the rhythm of a camel's hooves on the sand.. It is said that drum beats were used to keep the camels mesmerised throughout a long trip across the desert- at journey's end the drums would stop and the camels would drop down dead.

Indonesian Rebab

The rebab became a favourite instrument of the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire, and could be heard everywhere from the palace to the tea house.. The arab orchestra or group uses many drones, unisons and parallel octaves, giving a stirring, powerful sound, but it is mostly modal with little in the way of chordal movement. The rebab, though valued for its voice-like tone, has a very limited range (little over an octave), and was gradually replaced throughout much of the arab world by the violin and kemanche.

The Kemenche (Kamancha or Kamantcha in Azrebaijan, Kemanche, Kemence or Kemancha in Armenia, Kabak Kemane in Turkey, Ghijak, Gijak or Gidzhak in central Asia, Kemange, Kamanjeh, Kamancheh...take your pick!) is thought to have developed in Iran; its name is derived from two Persian words Keman (violin) and Ce (small). It can also be referred to as a Persian Spike Fiddle.

Like the rebab, it is held upright, has a body ranging from circular to an elongate boat shape and has been adopted and widely disseminated by the arabs, used in both classical and folk music.The spherical body is traditionally made from a coconut shell, with a face made from ox skin, or the skin of a fish (Siluris Glanis). The main difference from the rebab is that it has a proper fingerboard like a violin, making accurate intonation rather easier. It has three or four strings, giving it an extra range and versatility.Tunings vary, but in Tehran it is tuned the same as a violin, GDAE. Strings were originally of gut or silk, but nowadays players often use modern violin strings. It is quiet compared to the violin, with a taut, nasal sound. The close proximity of the strings allows double stopping, and drones, trills and other embellishments are widely used. It is often played in arab orchestras alongside either the rebab or violin, or sometimes both.

Munis Sharifov, Kemanche professor at National Conservatory of Baku, Azerbaijan John Vartan with Armenian Kemenche

In Ottoman classical music it is called the Klassikkemenche, though confusingly the Greeks refer to the same instrument as the Constantinople lyra or Politiki lyra. Originally a folk instrument, this was introduced to the art music of the Ottomans by the Greek gypsy musician and composer Vasilaki in the 19th Century. With the expulsion of the Greek population from Constantinople in 1923, the Politili Lyra fell into disuse, and only Lampros Lionatridis was playing the instrument up until his death in the 1960's. Today Sokratis Sinopoulos is one of the leading players, working both on the original "laiki" repertoire from Asia Minor; tsiftelia (belly dance music), taximi and karsilama- and also with modern fusions such as with modern Greek composers, with Loreena McKennitt, and Charles Lloyd's jazz quartet.

The Politiki Lyra is a small instrument, and because it does not have a nut, the middle string is longer than the other two and the fingering starts in a different position

IRANIAN KEMENCHE

The kemenche has a particularly strong place in Iran, where since the Islamic revolution in 1979 it is seen as representing traditional values, as opposed to the more decedent and westernised violin. This Persian Kamenche has a round body, a long neck, and four strings; in shape, in fact, it looks far more like a rebab.

The Kemenche is also important in the Pontic areas of the Black Sea (settled by the ancient Greeks). Here a long 3-stringed version, usually tuned in fourths; GDA or AEB, is called the Black Sea Fiddle, Pontic Lyra, Pontic Kemenche, Kementche of Laz, or Karadeziz Kemencesi.

Black Sea Fiddle

The extensive use of double -stopped parallel 4ths is an important feature of the playing of this instrument, with lots of trills on the upper notes. The strings are pressed straight down onto the fingerboard like a violin, making this much easier to play than most of the other lyras and kemenches, despite being held upside down on the knee.

The music tends to be fast and energetic, with tunes in 4/4, 5/4, 7/8 and 9/8.

Adib Rostami playing Kamenche at the London Fiddle Convention, 2011

In Iraq a version of the instrument is called a Jose or Josa. It is used as part of the unique Iraqui maquaam tradition; this is a vocal tradition, based on a repertoire of 56 songs- some old, some from the early 20thC. The Josa is often used for accompaniment of these songs. The santur (a type of dulcimer), and percussion, are sometimes also used. Most of the musicians playing these songs in Iraq were Jewish, up to the 20th C. Performances are mostly in coffee shops or in private homes, with concerts often lasting all night until morning.

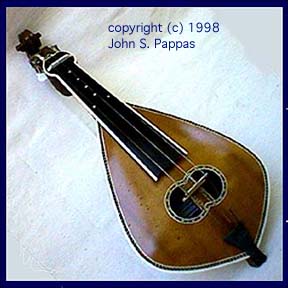

Cretan Lyra

On the Greek island of Crete, the lyra (pronounced lee-rah, and nothing to do with a lyre!) has become something of a national

symbol. It has a small, pear-shaped body and a very short neck. Constructed of mulberry wood, ivy or wild pear, it has two semicircular sound holes or "eyes". It looks in fact very similar to the Bulgarian gadulka, but does not usually have the sympathetic strings.

Cretan Lyra by M. Stagakis, 1981

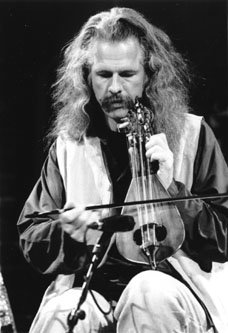

Ross Daly The Calabrian Lyra

Close relatives of the Cretan lyra exist in various parts of the Mediterranean, notably in Calabria, the "toe" of Italy. A few years back I met the musician, journalist and anthropologist Ettore Castagna, who among many other ethnic instruuments of the region is a fine proponent of the "lira calabrese". I was also contacted by Savior Gerace who sent me this video;

and here's a photo of his lyra, which he says some people call the "Violin of St.Hole" The length of the Calabrian lyra can vary, and with it the tuning.

Confused?

Having read this far you are probably thoroughly confused about what is a rebab, what is a Kemenche, and what is a lyra, and whether or not you tell just by looking at them...You may even come across the term spike fiddle which may include almost any of these. Happily I can report that even the experts (and you can count me out here!) seem equally confused. Suffice it to say that there seems to be no consistency in the naming, classifying, or indeed spelling of this family of instruments.The European violin, finally, finds a place alongside its more primitive cousins, having been brought to Egypt during Napoleon's campaigns and to Constantinople by professional Greek and gypsy musicians. It has been adapted to suit the modal nature of arab music by an extensive range of retunings (in Iran, for example, ADAD, GDGD, GDAD and EDAE are all common) Playing is often highly ornamented with slides,

double stops, wide vibrato, open drones and so on, and whilst the violin is sometimes played under the chin, it may also be played upright, as in Morocco or sometimes Turkey.There is an interesting and unusual tuning widely used in Greek and Turkish violin music, called Çifte Telli (or Tsifte Telli). It is a GgDd tuning, and involves crossing the middle strings both above the nut and below the bridge. To achieve this, the middle strings are first loosened, then without removing either string from the pegs, they are swapped into each other's notch in the nut, The same is done at the bridge end , again without removing the strings, so that the strings swap notches in the bridge. This leaves two X's where the strings cross above the nut and below the bridge.. The G string remains on G; the next string is tuned to G an octave higher; the next string agin becomes a D, and the top string A D an octave higher.

By double-stopping the 1st and 2nd or 3rd and 4th strings an octave can be played, giving a distinctly oriental sound. Double-stopping the 2nd and 3rd strings gives an unusual harmony of parallel 4ths- a very primordial sound on which Black Sea fiddle music is based.

The name of this tuning Çifte Telli is Turkish for "double strings". It appears in Klezmer as tsvei shtriens (two strings), and also features in gypsy and Romanian fiddling.

One of the leading Greek fiddlers in Britain is Michalis Kouloumis. He drew my attention to this recording on his debut album "Soil", in which he uses a different Çifte Telli tuning from the one described above. G and D are as normal. The A string is tuned down to a lower octave E, and moved towards the normal E so they can be played simultaneously.

He has heard this tuning used on vinyl recordings of early Greek violinists such as Demetris Semsis, Giannis Ogdontakis, Demetris Manisalis, Giorgos Koros. It was introduced to Greece from Asia Minor.

Links:

- The Rebab (from "staying in tune"

- Magrini's Lyra page

- Trehantiri; Best source for Greek and Turkish music

- Ross Daly

- Leigh Cline's Pontic Music page

- John Vartan's page of Armenian folk instruments (including Kemenche and Black Sea Fiddle)

- Parham Nassehpoor' s page on Persian music, including Kemence

- "Stagakis" Cretan Lyra workshop

- History of the Cretan Lyra

- Kemenche

Return to fiddlingaround.co.uk homepage