MENU TO FIDDLE STYLES:

Scandinavian fiddle

In Scandinavia the fiddle is quite literally the stuff of legend. The wild landscape of air, rock , forest and water is reflected with crystal clarity in the bleak majesty of the music, and tales abound of the supernatural link between the fiddler and the twilight world of devils, sprites and trolls.

Norwegian Fiddle; The Hardingfele

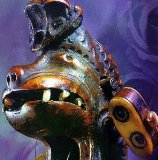

The Norwegian folk tradition centres around its unique national instrument, the Hardanger fiddle or hardingfele, thought to have been first developed as early as 1650. The oldest known instrument is the famous Jaastad fiddle, dated 1651, built by Ole Jonsen Jaastad (1621-94); he was a sherrif from Ullensvang in Hardanger. The instrument soon caught on, and in the 18thC the fiddle maker Trond Botnen is said to have produced 1000 hardanger fiddles. The earliest Hardanger fiddles were much smaller than either the modern hardanger fiddles or standard violins, and they were more rectangular in shape. The most significant difference between the Hardinfele today and the standard violin is the presence of four or five sympathetic strings which run under the fingerboard. These ring freely whilst the fiddle is being played providing eerie drones, harmony and sometimes unexpected dissonance, apparently above and beyond the control of the fiddler. The pegbox is longer than on a violin, and the neck is shorter (as it was on all early violins), so that playing is laregly confined to the lower positions. The bridge and fingerboard are also flatter to facilitate double and triple stopping. The body is richly decorated with black ink (a technique called rosemaling); the fingerboard and tailpiece are inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and the headstock is carved into the shape of a maiden, dragon or lion's head

There are over 26 different tunings for the hardingfele, each of which has a unique voice and leads to a different set of tonal possibilities. Just as individual raags are associated with particular times of the day, so hardingfele tunings take on a semi-mystical quality, with names such as "twilight grey", light blue and "half-troll tuning". A few common examples include ADAE (oppstilt or hØgbass.);GDAD (spakrostilt); DDAE (Lausbas- loose bass); or AEAE (halvt-trollstilt). Be careful with AEAC# (Nackastamning)- this is the devil's own tuning! The sympathetic strings on the hardingfele are retuned depending on the main strings, but the standard tuning is (B)DEF#A which, surprise surprise, gives the opening phrase of Greigs's Morning from Peer Ghynt!

The hardingfele is often tuned rather higher than standard pitch to accentuate the bright ringing effect. Many tunes also use a non-standard scale including quarter-tones; this may be an ancient inheritance from the primitive selje floyte (a one-holed willow flute) which appears to have a natural rather than man-made register. That these eccentricities have survived is partly due to the fact that the hardingfele is traditionally a solo instrument and has not had to face up to the teutonic tyranny of the accordion; also the natural barriers of mountain, fjord and forest have effectively kept many communities quite isolated until recently, allowing local styles to thrive and diversify.

The best collection of Hardanger fiddles today is found at the Folk Museum in Utne on Hardanger Fjord.

Probably the greatest hardingfele player Norway has known was Torgeir Augundson -Myllargurtan ("Miller's Boy"), who from 1830 to 1850 dedicated his life to travelling the country learning and exchanging tunes, embroidering and personalising them in a remarkable way, and bringing the instrument for the first time to the concert hall. It was he who introduced the idea of lydarslater- tunes for listening rather than dancing. He benefited from the movement of Romantic Nationalism sweeping Europe at the time; in Norway this led to a greatly increased interest in traditional folk music, and saw the Hardingfele being referred to as the National Instrument. The first solo Hardanger Fiddle concert took place in 1849 in Kristiania.

An important development in the furthering of the Hardingfele tradition came in 1888 with the creation of the first kappleik, a judged contest, focussing on Hardanger fiddle. It was held in Bo, Telemark. Local and national contests have continued ever since, helping to focuss attention on technique and repertoire, and encouraging the raising of standards.

The fiddle and the Church:

As in many European countries, the fiddle was a target for disapproval by certain branches of the church. This was particularly so as so many pagan and devil-related myths were attached to Norwegian fiddling. In the early to mid 1800's a religious movement called The Pietists, lead by Hans Nielsen Hauge, spread through rural districts of Norway. The Hardanger fiddle- "the devil's instrument", was highlighted as a source of sinful activity related, as ever, to drinking and fornication (yes, all the good things in life!), and fiddlers were driven to stop playing and often to destroy their instruments.

The West of Norway was hit by famine around 1850 and, as in Ireland, there was a great emigration, particularly to the American midwest. As a result a strong hardingfele tradition became established, and still survives, in the USA.

In 1923 the Norwegians realised that their musical traditions were in danger of declining, and a deliberate revival was started, with the creation of a national fiddlers association, the Landslaget for Spelemenn. Classical music students were encouraged to learn hardingfele alongside the standard violin. Government support for folk music remains strong in Norway to this day.

One of the most influential players currently is AnnbjØrg Lien , who works with her group Bukkene Bruse. Knut Buen and Hallvard T Bjorkum are other fine players. You can hear Knut Buen in an interesting "experimental pagan folk metal" context (yes, such a thing does exist!) on the album Grimen with the band Hardingrock.

You can also hear the Irish fiddler Dermot Crehan playing hardingfele on the soundtrack of The Lord of The Rings (The Two Towers). The instrument takes the main theme for the Rohirrim- the blue-eyed, blonde haired horsemen (Norsemen?) of Rohan.

AnnbjØrg Lien

Legends

Some hardingfele tunes are rhythmically very complex. The springar, though basically in 3/4, appears virtually impenetrable, with beats which vary widely in length; it is nevertheless a dance tune and is accompanied by foot stamping. More accessible are the different types of walking tune, from the slow march to the gangar, a steady 2/4 or 6/8. The halling is another 2/4 tune, played for a solo dance where a man attempts to leap high enough to kick a hat off a stick held by a girl. The origin of some of these old tunes is cloaked in legend. One tale tells of the Fossegrimmen, a water sprite that lives in a waterfall, who will teach you a tune in excahnge for a leg of lamb thrown into the torrent. If the lamb isn't thought to be of suffiecient quality, all you'll get is the ability to tune your fiddle. Another tells of the troll or Nacken who lives in lakes and streams; if you hang your fiddle overnight under a bridge where he lives, the troll will retune your fiddle and play a tune on it, finally leaving his own instrument next to it. If on returning you pick up your own fiddle, the troll's tune and supernatural touch will be yours. If by mistake you pick up the troll's fiddle, your soul is his forever!

Rammeslatter are tunes which, because of their hypnotic quality can put player and listener alike into a state of trance; the fiddler will play, unable to stop, until someone drags the fiddle from his hands. Julane Lund, a fiddler who studied traditional arts at Telemark University, has recently studied this phenomenon and finds it to be both real and observable; the player himself will often come out of the trance feeling exhasted, and having no memory of playing. Legend says that fanitullen, the devil's tune, was first played by the man himself who appeared, hooves and all, at a village dance. He grabbed the fiddle and began playing a tune so wonderful that the gathered people continued dancing until they died from exhaustion- and then their corpses continued dancing until their skulls rolled out of the door and down the hill!

Another group of tunes, the Gammeldans, were imported from Sweden in the 19th century; these tend to be more predictable and less mysterious and melancholy. The mazurka has a bouncy 3/4 rhythm (eg. Brage Gilles Mazurka); a similar dotted rhythm, but in 4/4 is found in the schottische (eg. Schottis fran (from) Lima.) Polkas, (not to be confused with polskas) and Reinlenders have a jolly 2/4 rhythm. Sweden has its equivalent to the walking tunes of Norway, including the brudmarsch (wedding march) and the ganglat. GardebyLaten is a ganglat so often played that people sing along with it words which mean "aren't you sick of this tune yet?". Also well known is Appelbo Ganglat . Probably the most important group of Swedish tunes are the polskas. These have a 3/4 rhythm with stress on the first and third beats; the emphasis of these beats varies considerably from region to region. Polskas, and indeed many Scandinavian tunes, are often named after a revered fiddler from the past whose playing defined a particular tune, though he is unlikely to have actually written it; for example Polska efter (after) Karl Linblad, or Polska e. Per Osa . Very useful for the fiddler is the skanklåt- an "I want to get paid " tune which reminds the guests at a wedding that the poor musician has been playing for five hours, hasn't been offered any sandwiches, hasn't been paid, and wants to go home. Most of the above Swedish and gammeldans tunes are played on the normal fiddle (called flatfele in Norway), often in ensembles with other instruments such as accordion, recorder, or fattigmannsfele (poor man's fiddle)- the jew's harp. Spellmannslag are large groups of fiddlers who meet regularly to learn, play for enjoyment, and maintain the tradition.

SWEDISH FIDDLE

The fiddle probably first arrived in Sweden in the 17thC from France, brought by musicians hired for the court of Queen Kristina.

It soon filtered down to the rural population, becoming established as the primary instrument for dance music. The oldest Swedish tunes, from Medieval times, show a close relationship to sälgflöjt (willow flute) and säckpipa (bagpipe) music, and to herding calls and simple songs. These tunes tend to be harmonically very simplistic and are built from very short formulaic phrases. Such tunes were easily adapted for the fiddle. However, the pre-classical baroque feel and structure of the music first played in the court remained a feature of much of the subsequent Swedish repertoire.tablished as the primary instrument for dance music. The oldest Swedish tunes, from Medieval times, show a close relationship to flute and bagpipe music, and to herding calls and simple songs. These tunes tend to be harmonically very simplistic and are built from very short formulaic phrases. Such tunes were easily adapted for the fiddle. However, the pre-classical baroque feel and structure of the music first played in the court remained a feature of much of the subsequent Swedish repertoire.

Grace and elegance are adjectives which are more relevant to Swedish fiddling than to many other styles. Linear structures and relatively complex melodic lines are a feature of many of these tunes, with development of themes, a wider range, and clearly defined harmony with arpeggios. This group includes the Polska, by far the most important group of tunes in Swedish fiddling. The third significant group of tunes arrived in the 19thC, largely imported from other parts of Europe; these included the waltz, polka, mazurka, hambo and Schottis.

These were relatively simple, accessible tunes, and with them came “modern” instrumentation including brass and the accordion. These instruments, and the general nature of the tunes, had the effect of “ironing out” many of the peculiarities of rhythm and intonation which had been an important part of Swedish music.

In common with many other European countries, the first serious interest by the intelligencia in folk music in Sweden began with the concept of romantic nationalism in the early 19thC. A search began for music that could represent the soul of the nation, and the newly formed Gothic Society (Götiska Förbundet) began collecting and publishing the oldest Swedish fiddle tunes they could find. The turn of the century saw the first serious promotion of live public performances by Spelmän (folk players), the first Spelman contest and the first national gathering of Spelman. Tune collection cumulated in the publication, between 1922 and 1939, of "Svenska låtar" ("Swedish tunes"), with 8000 songs and tunes from around the country. Even this collection was not complete, and several regions in the north were left out when the collectors ran out of time.

In the 1937 the first Spelmänslag was formed, an amateur group of mostly fiddlers who got together regularly to practice and perform. Many of the players were from a classical background. The idea was so popular that similar groups rapidly sprang up across the country. The majority of the music of these groups is unison fiddles, though some harmony is also added, and in recent years other instruments such as guitars, accordions, double basses and drums can also be included.

The spread of Spelmänslag coincided with a general move away from solo fiddling, which had been the norm, towards widespread harmony twin fiddling. Playing harmony fiddle is known as Tersstamma Sekundeering. This can be simple harmonies a third above or below, or a more complex line involving double stops with short lines joining the chords.

Twin fiddling grew in part grew out of the tradition that some professional fiddlers would have a child apprentice who would learn to play harmonies along with the master. At weddings two fiddlers playing on horseback would sometimes announce the arrival of the bride and groom. Fiddling whilst walking also happens, especially when a fiddler leads people to the church for a wedding, or on the occasion of midsummer festivals when an audience has to be moved from one location to another. This can happen even with massed fiddlers in a Spelmänslag.

The “Green Wave” of the 60’s and 70’s brought a further widespread interest in regional and local culture, and the end of the 20thC saw further consolidation of the fiddle revival. Young, musically literate players like Mats Edén persuading the music education establishment that folk fiddling was as rich and complex in its own way as classical “art” music, and equally worthy of funding, research and concert-hall performance. This depended in large part on sophisticated and apparently accurate transcription of the richly ornamented playing style of traditional fiddlers- something that had previously been an entirely aural tradition.

SWEDISH FIDDLE ORNAMENTATION

Swedish fiddling is rich in grace notes, rolls and trills, double string unisons and drones, and notes raised or lowered by micro tones. The word drill (trill) is used as a general term to describe all of these.

Description of Swedish fiddle ornamentation is made difficult by the fact that different fiddlers in different regions use different names and different approaches. How to decorate a melody is often down to personal choice. To quote Mia Marine;

“The vocabulary around ornaments is also very confusing. If you just search on Youtube, you will hear very prominent musicians saying totally different things about what the ornaments are called and how they are played.”

One of the most common ornaments is the förslag (“before-hit”), similar to the hammer-on or pull-off seen in both Irish and American fiddling. Where there are two adjacent notes of a different pitch, the first note is repeated as a short grace note, tied to the next note. The leading or grace note may also be unrelated to the previous note; a first finger melody note may be preceded by an open string grace note; a second finger melody note by a first finger grace note, and so on.

Also very common is the lower mordent, where a melody note is very briefly interrupted by a light flick of the next note down in the scale, or a note a semitone below.

Rolls in Swedish music are not unlike those in Irish music; I am assured by Mia Marine that they are referred to as pretzels.

Trills, which are a very characteristic feature in Sweden are never heard in Ireland. They can be either upper or lower trills, depending on whether the melody note is the lower or upper. The trill can be with two beats or notes, or three or more, and the grace notes can be either above or below the melody note.mThe direction of these trills is largely a matter or personal expression. The wider the musical interval between melody and grace note in a trill, the greater its expressive effect. The trill may also accelerate towards the end of the note.

The fourth string/open string unison is common to both Sweden and Scotland, and Swedes often use this on a longer note to rock backwards and forwards between strings, adding a rhythmic pulse within the length of the note. This pulse can also be accentuated with a break note- a single flick of an upper note, not unlike the cut in Irish music. The second half of the pulse, half way through a long bow, may marked by a sudden increase in bow speed, similar to the “updriven bow” in Scottish strathspey fiddling

The Swedes also make great use of the “ringing strings” which are also a feature of Shetland fiddling. This can involve either single open strings, or extended open string drones. Keys which allow extensive use of open strings are preferred; mainly G, D and A.

Like in Norway, Swedish fiddlers often use the natural or untempered scale. This means that some notes are played slightly sharp or flat to what you would expect, for example, from a conventionally tuned piano. This relates partly to the extensive use of open strings, to the historic link to sounds such as the willow-bark flute, and to the early tradition of fiddle as a solo instrument. As an example, the (normally) flattened seventh note of a minor scale, is often played slightly sharp, especially if it is leading up to the tonic. Sometimes the tuning will be different going up to coming down. The beauty and subtlety of the natural scale is lost with large ensembles, particularly where tempered instruments such as the accordion are involved. Fortunately, fiddlers greatly value these special notes, and they are unlikely to disappear.

The Polska

One of the greatest challenges for outsiders when trying to understand Swedish music, is the rhythm of the polska. This is a dance known in Sweden since the end of the 15thC, and it has remained popular up to the present day. Written conventionally in ¾ time, they can appear on sheet music perfectly straightforward. However, there are different forms of polska all round the country. With triplet polkas each note can be divided into three, while 16th-note polkas have each beat split four ways. Whilst some have three equal beats (even polskas or jämn polskas), others are uneven (ojämn) have a second beat which is moveable.

Swedish Fiddler Karen Myers explained to me:

"Examples of very asymmetric styles are Boda polska, Orsa polska, Södra Dalarna polska. This is one of the reasons that the typical fiddler foot-tap for polska is on the 1st and 3rd beats, since that 2nd beat could be all over the landscape, depending. Moving the timing of that 2nd beat is an expressive opportunity for the musician, very similar to pressing the leading notes in a melody up or down."

The second beat is often the one where dancers lift their feet (eg on the bodanpolska); depending on how the dancers move, the fiddler may delay this second beat to stay in time with the dancer’s feet. A similar thing is sometimes seen in English Morris dancing. With some polskas the rhythm works in two-bar patterns, with the first bar being asymmetrical, the second more even. There are thousands of polskas in Sweden, and each region has its own repertoire and style. Many tunes are traditional, but, as in Norway, are named after a particular fiddler who made a particular version popular. For others the composer is known.

Mia Marine suggested to me that Polskas are in fact over-represented in the repertoire, having been widely collected in the past at the expense of other tune types not because they were widely played, but because they were seen as the oldest, and therefore purest type of Swedish tune.

SWEDISH FIDDLERS

Olaf Jonnson From, an exceptional 19thC fiddler in Häslingland in central Sweden, was much in demand to play for weddings; part of his success may have been down to his compositions; as part of the deal, he would write two new tunes for every wedding he played at. Since he is said to have completed 416 weddings, that’s a sizeable contribution to the national repertoire!

One of the first fiddlers to achieve national fame was Hjort Anders Olsson (1865-1952). He came to the attention of tune collector Nils Andersson, who recorded and transcribed many of the tunes from Olsson’s repertoire, particularly those of his home village of Bingsjö. He was invited to compete in one of the first national fiddler’s contest in 1908, and won first prize, after which he toured several times, often with other fiddle players. He left many recordings, and a wealth of his own compositions, including Twelfth March. The ubiquitous Gärdebylåten may also have been his.

One of the most important contemporary Swedish fiddle players is Mats Edén, one of the first folk fiddlers to be accepted into the “art” music establishment. His playing is rooted in the folk tradition of Värmland (in western Sweden). He has been a Riksspelman (National folk musician) since 1979; is a professor, and member of the Swedish Royal Academy of music. He is a member of the band Groupa, as well as being involved with many other writing, performance and recording projects.

Nyckelharpa

Sweden has its own unique fiddle in the Nyckelharpa. This has tangents, acting like frets which can be raised or lowered with keys instead of fingering the notes directly onto the fingerboard. In the modern chromatic version of the instrument there are three melody strings, one drone string and twelve sympathetic strings. The instrument has a 3 octave range.

Another interesting fiddle variant in Sweden is the träskofiol or wooden shoe fiddle. Found mainly in the South of Sweden, this is a budget fiddle whose body is constructed from a used wooden clog. Though rather quiet, and often tuned low, they are perfectly playable fiddles.

The Swedish fiddle tradition is surely one of the richest and most challenging, and yet by comparison with the music of Ireland, for example, is scarcely on the radar outside of Scandinavia. It deserves to be better known!

If you want to learn to play Swedish fiddle properly, I suggest you try Mia Marine’s Fiddle Academy at https://www.fiddleacademy.com/.

And for a huge online collection of tunes, try folkwiki.se

Finnish fiddle

Finland, lying between Sweden to the west and Russia to the east has a tiny population of under 6 million, but punches well above its weight when it comes to fiddling. There are two major folk traditions in the country

1.The Kelevalaic. This is the older of the two, mostly involved with vocal tradition and the telling of epic folk poems

2. The Pelimanni or Nordic; dance music imported from central Europe via Scandinavia in the 17thC. The term Pellimanni is Finnish for Spellman (musician). Fiddles dominate this tradition, along with clarinet, harmonium and accordion. Dance forms include the polska, polka, mazurka, minuet, quadrille, waltz and schottische; a very similar mix to the gammaldans repertoire of Norway and Sweden.

The region of Kaustinen has become the focus for Pelimanni music, with the Järvelä family (hailing from the village of that name) forming an important fiddling dynasty. Antti Järvelä (1876-1955) was a famous wedding fiddler; buth his son Arane and grandson Johannes became mestaripelimanni (master fiddlers). Son of Johann is Arto Järvelä, considered by many to be Finland’s leading fiddler. He became a founder member of the band JPP; Järvelän Pikkupelimannit, 'the little fiddlers of Järvelä'. This group, with its multi-fiddle lineup, expanded the range of Finnish music with rich orchestral textures and adventurous compositions.

Three more young fiddling Järvelä’s-Antti, Esko and Alina are at the core of the latest Finnish sensation, Frigg. The Sibelius Academy of Helsinki has been an important feature in the ongoing development of Finnish music, the folk music department there stressing the importance of forward-thinking composition, arrangement and studio production, as well as the maintenance of tradition. An interesting feature of Finnish fiddling is the recently revived Jouhikko, a bowed lyre closely related to the kantele. It has 2 or 3 horsehair strings, played with the back of the fingernail. The foremost exponent of the Jouhikko is RaunoNieminen of the group Jouhiokestei

.

Jouhikko

________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

Links:

AnnbjØrg Lien homepage

The Hardanger Fiddle Association of America (HFAA)

Swedish Traditional Music page (includes musical examples of different types of polska)

Lennart Sohlman's Swedish Fiddle Site

Karen Myers; "Blue Rose" Scandinavian music site

_______________________________________________________________________________

RETURN TO FIDDLINGAROUND HOMEPAGE

Welcome to the spirit world. This is an album which still has the power to send a chill down my spine, years after having first heard it. With 16 tunes collected from different artists across the country, it captures the mystery and otherwordliness of Norwegian fiddle music. There is a broad range of material here; some are tracks on solo hardanger fiddle (eg the fossgrimhallingen- waterfall wizard’s tune), solo “standard” fiddle (Fanitullen- the Devil’s Tune); there are twin fiddles (Kvernknurren- the Mill Sprite), and some band arrangements, with guitar, mandola, flute or kantele. Every tune is a gem, but among my favourites are Einar Mjolsnes’ Goat’s Tune, with its alternating pizz and arco sections, and Knut Rieiersrud’s Springar Dance in Gjermund’s tuning, a trance- like piece with a baffling rhythm, and dark chord changes provided by a bowed bass.

What all the tracks share is the almost magical use of complex retunings, dictating wild and unpredictable harmonies, plus the trills and drones which carry this music so far from the world of celtic and American fiddling. Bernt Balchen’s fascinating liner notes introduce us to the history and mythology of Norwegian music, and to the different tunings and rhythms, all of which contribute to the hypnotic quality of these tunes and their deep connection to the landscape of Norway.

Frigg; Polka V

From the outset you know this is a band with attitude. The first track, Vierivä (The Rolling Schottische) opens up with a barrage of power chords as meaty as anything from a 70’s heavy prog rock band. But Frigg are all about texture, colour and contrast and as one twisting, sinuous melody leads to another we are lead through an array of spacious soundscapes. Some are quirky and tongue in cheek, such as Polkka V (Displeasement Polka), and Big Brother, but others, such as Teppo’s Waltz, are so melancholy and beautiful it almost hurts to listen to them.

Unison fiddles take the bulk of the melodies, accompanied mostly by bass and cittern. Though steeped in the Pelimanni tradition of Kaustinen, Frigg write most of their material, and take on board a host of outside influences. Most notably there are moments when you would swear that Messrs Grisman, Douglas, Rice and O’Connor had slipped into the studio as the band take a detour into Nordgrass. Hats off to whoever took the luscious fiddle solo in Vuodet Rääkylässä.

I don’t often get the shivers when I hear a new album, but this did it for me.

On this, their eighth album, Finnish folk group Frigg continue to step with confidence and authority through a variety of genres. Home territory for them is the polskas and waltzes of Finland and Scandinavia, but they are known in particular for their affinity with the more modern side of American bluegrass.

There are excursions into celtic (such as Chris Stout’s compliments to the Bon Accord Ale House, and Tasajalka-Salminen ), rock (Friggin’ Polska), and Balkan (False Legenyes). The soaring and sweeping of four perfectly blended fiddles gives a cinematic grandeur to many of their compositions, and their music is full of changing textures and surprising corners.

It’s not all about massed fiddles; there are beautiful and intimate mandolin solos on Yöjuoksuvalssi / Courting Waltz and on Taivalkoski. Vonkaus has a lovely contemplative bass solo, while the fiddle solo on Tasajalka-Salminen is worthy of Stuart Duncan or Mark O’Connor.

Majestic and deeply satisfying.

.jpg)